Constraining LLMs for Perfect Monospace Text Formatting

Published:

Typesetting is notoriously hard to do well. This is especially true when typesetting fully justified text, i.e., text that is aligned to both the left and right margins of a column. It’s all too easy to end up with large spaces between words, giving an ugly appearance, for example:

In situations where you’re stuck with a given width, the only way you can fix this problem is by rewording the sentence. Now imagine doing it with monospace fonts, where you can’t even change the size of spaces between words and your only option would be to get the character count of each line exactly right. This is possible for people to do, but it’s a lot of work. Fortunately, we can train LLMs to do this for us!

In this post, I’ll show how constraints can be added to LLM text generation to ensure perfectly justified monospace text.

This project was inspired by this video by Tom Murphy VII (aka suckerpinch). In it, he references the incredible effort of the GameFAQs Metroid speedrun walkthrough author rs1n, who wrote an entire walkthrough for Super Metroid in monospace text such that every line was exactly 75 characters long. In the video, he shows how this might be done with an LLM, having it generate sequences of text until they get a word break at the right point. However, this process is still overly manual, so I decided to see if I could automate it, producing perfectly uniform blocks of coherent text with no human intervention.

To show how I achieve this, I’ll start by showing why the standard greedy text generation approach doesn’t quite work, before looking at how the slightly more complex beam search can be adapted to the purpose.

Greedy Generation

In its simplest form, LLM text generation works by breaking an input text into tokens, fragments of words each a few letters long, then given the current sequence of tokens, predicting what the next most likely token should be.

For instance, if we have the incomplete sentence

In Star Wars, Mark Hamill plays…

The tokenizer would break this down into individual tokens: 1

[’<s>’, ‘In’, ‘Star’, ‘Wars’, ‘,’, ‘Mark’, ‘Ham’, ‘ill’, ‘plays’]

The LLM would then iteratively predict the next most likely tokens until it completes the sentence.

The following shows what the text generation process would look like starting from “Mark Hamill” (given an appropriate prompt):

We can see that at each stage, the LLM generates probabilities for all possible next tokens, and chooses according to the given probability distribution (or it can be made to always just choose the most likely token, which is what we do here).

But notice that the tokens don’t all correspond to the same number of characters. In the TinyLlama tokenizer, for instance, the longest tokenized words are 14 characters long (e.g., “straightforward” and “representations”), and the longest tokens correspond to 16 characters, though these are mostly strings of punctuation.

This causes a problem for us if we want to enforce a maximum line length. It means we can’t just count the number of tokens that we’ve used to determine how far along in a line we are, we need to count the number of characters. There are two naive approaches that we might consider:

- Just sample randomly until we get a sentence that fits neatly on the line. Then move onto the next line

- When we get near the end of a line, choose the most likely token that doesn’t go over the line length

In his video, Tom Murphy used the first of these approaches, and it works reasonably well. But having to resample multiple times is slow and inefficient, so we’d like to avoid it if possible.

The second approach might sound reasonable, but we run into a different problem. What if we’re halfway through a word? Since the LLM gives a distribution over all tokens, it will find a token that fits, but say we have one character left after “In Star Wars, Mark Hamill plays Luke Skywalk”, there aren’t any good options; the only reasonable completion is “Skywalker”.

So this isn’t ideal either. Instead, it would be good to be able to leave our options open so we don’t have to backtrack when we hit dead ends that result in having to settle for nonsenscal shorter completions like “Luke Skywalks”.

Beam Search

Rather than greedy text generation, we might want a method that can keep multiple candidate generations in mind, so that if one turns out to be a dud, we have other options to fall back on. Beam search does exactly this, considering multiple options, or beams, simultaneously, keeping the most promising at each stage while discarding those that stop looking viable.

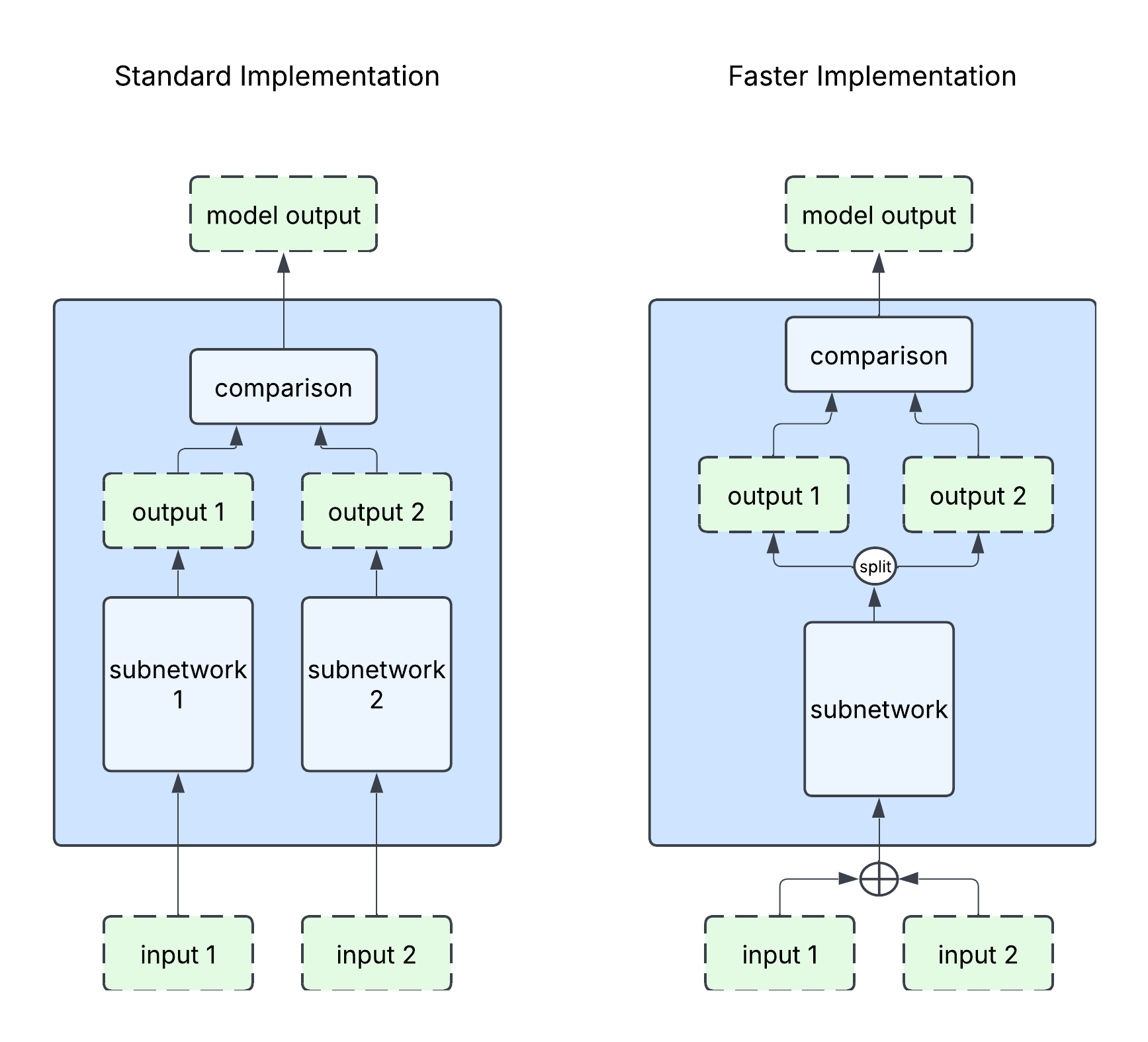

We will shortly look at how beam search can be adapted for our purposes, but first let’s look at how standard beam search works.

In beam search, rather than generating a single most likely sequence, at any given step of the text generation process, we consider \(k\) possible candidate sequences. If we have a vocabulary of \(V\) tokens to choose from, then in beam search we would do the following:

- In the first step, calculate the probabilities of all possible next tokens, choosing the top \(k\) most likely tokens. This is the same as the first step in our greedy generation process.

- In subsequent steps, for each of the \(k\) beams, we calculate the probabilities of all possible next tokens. This gives \(k \times V\) possible completions. Then across all beams and all next tokens, we choose the top \(k\) most likely completions to serve as our beams in the next stage.

This is visualised below:

Beam search is still fundamentally greedy, we only keep a finite number of the most promising paths, abandoning others that may ultimately end up being better but look poor in the short term. But if it hits dead ends, it is still able to backtrack a little, it should give us a better chance of success once we’ve implemented our formatting rules.

Adding Constraints

We now need to consider how our constraints on beam search should be constructed.

Getting the text generation to take up an exact number of characters on each line means that we need the following constraints:

- The next token cannot cause the current line to exceed

line_lengthcharacters long - The next token should be a newline if the current line is exactly

line_lengthcharacters long - The next token should not be a space if it will complete the current line

The last of these constraints is not strictly necessary, but ending on a space detracts from the otherwise uniform appearance of the text.

Practically, we implement these constraints by penalising any sequences that violate them by giving them a probability of zero. This means that literally any sequence that doesn’t violate those constraints will be considered more likely, and, therefore, only perfectly formatted sequences will be selected.

I’ll show the technical details of how this is done later, but for now, let’s look at some examples of how these three changes can make a dramatic difference to the output.

Some Examples

For the following examples, I use mistralai/Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.3 as my model and generate the new typeset text using the following prompt template.

Paraphrase the following text:

{TEXT TO PARAPHRASE}

You might notice that we just tell it to paraphrase the text, rather than saying anything about adhering to the formatting constraints. This is because the constraints are in the generation code, the model doesn’t even need to know about them, and yet any outputs from the model will perfectly adhere to them.

For our first example, here is the introductory paragraph to the Wikipedia article for Hot Fuzz:

And here is the opening to the text of Alice in Wonderland:

In both cases, the paraphrasing is surprisingly accurate, and the generated text is perfectly aligned.

However, this is not always the case, sometimes the model appears to get a bit stuck and resorts to splitting words over multiple lines in a way that feels unnatural. For instance, this attempt at paraphrasing the Wikipedia synopsis of The Hobbit:

Unfortunately, this kind of problem is far more frequent than I would like in the outputs. There can also be other artefacts like in this paraphrasing of the Wikipedia article for beam search. In the example below, the paraphrasing is generally competent, but it gets somewhat confused trying to use the word “node(s)” as a way of taking up the last few characters of a line. It’s also hallucinated a reference, which feels pretty typical LLM behaviour.

I think that changing to a larger model may help improve the quality of the output, though I also think that beam search might not allow quite enough backtracking for the algorithm to get out of potential dead ends. Indeed, to get the best chances of success, I found it was usually necessary to have an unusually large number of beams (often ~100). There are a couple of options in the literature for variations on beam search that offer more diversity between the beams (e.g., this one), though I’ll leave this for someone else to explore.

Overall, the current results are far from perfect, but for a relatively small model, I think they’re still pretty impressive.

Implementation Details

I have released a full implementation of this new beam search in this repository, with examples. Here I’ll show the key part of the code, which occurs inside the function which determines which \(k\) continuations should make up the beams in the next stage of the search.

# get_whitespace_token_ids is a function which

# tokenizes a newline and a space to get their ids

newline_token_id, space_token_id = get_whitespace_token_ids(tokenizer)

token_lengths = torch.tensor(

[token for token in tokenizer.convert_ids_to_tokens(range(tokenizer.vocab_size))],

device=device,

)

# We calculate the length of the current line in each beam using the function `line_lengths`,

# this function searches for the last newline token, then decodes the tokens from that

# point, returning their length

beam_lengths = line_lengths(running_sequences, cur_len, tokenizer, newline_token_id)

log_probs = accumulated_log_probs.reshape(batch_size * num_beams, vocab_size)

# Set all logits that would extend beyond line_length to -inf

log_probs = torch.where(

beam_lengths.reshape((-1, 1)) + token_lengths > line_length,

torch.tensor(-torch.inf, device=device).reshape((1, 1)),

log_probs,

)

# If at line length, set all logits that aren't newline to -inf

# This corresponds to giving them probability zero

log_probs = torch.where(beam_lengths.reshape((-1, 1)) >= line_length, -torch.inf, log_probs)

# If at line length, we give the newline token a probability that a space token would usually have

log_probs[:, [newline_token_id]] = torch.where(

beam_lengths.reshape((-1, 1)) >= line_length,

torch.ones_like(log_probs[:, [newline_token_id]]),

log_probs[:, [space_token_id]],

)

# Don't allow line breaks in the middle of a line, but allow them at the beginning

log_probs[:, [newline_token_id]] = torch.where(

torch.logical_and(0 < beam_lengths.reshape((-1, 1)), beam_lengths.reshape((-1, 1)) < line_length),

-torch.inf,

log_probs[:, [newline_token_id]],

)

# Don't allow lines to end in a space.

log_probs[:, [space_token_id]] = torch.where(

beam_lengths.reshape((-1, 1)) == line_length - 1, -torch.inf, log_probs[:, [space_token_id]]

)

I’ve written the code in such a way that it can be used as a drop-in replacement for the standard beam search

in the Hugging Face transformers library. The only thing you need to do is in the generate function pass in the

new beam search function as the value for the custom_generate argument, as well as passing in a new

line_length argument.

Internally, the custom generate function is identical to Hugging Face’s standard beam search, except that it

has been modified to be a standalone function and it now calls a custom version of _get_top_k_continuations which is where the changes listed above sit. We also now pass it a

tokenizer to allow the function computing continutation access to information about how long

each line currently is.

Related Work

While to the best of my knowledge, this is the first time that monospace fully-aligned text has been automatically generated with an LLM, there are several similar projects that are worth mentioning:

First, there is the suckerpinch video that I mentioned earlier, where he does a very manual version of the same process. But this is only a small part of the video, he uses it as a jumping off point for a far more ambitious project than this one: BoVeX, an entire programming language and typesetting system designed to use LLM rephrasings to increase the aesthetic appeal of paragraphs written in non-monospace fonts. I definitely recommend it as a far more rigorous example of LLMs applied to typesetting.

In terms of constraints on text generation, this is something that Hugging Face does offer some support for different forms of constrained text generation. Early on, I found this article, published by Hugging Face, about constrained text generation. It looks like there is support for some constraints, like enforcing the inclusion of certain tokens in the generation process, but the constraints were not quite what I was looking for.

There has also been some great research from Anthropic looking at how LLMs manage to do reasonably well on this task even without the benefit of constraints on the generation function. It is undeniable that LLMs have some capacity to tell approximately where a line should break, though my attempts at prompting Opus 4.5 to explicitly break at exactly 30 characters showed that it is not a skill that comes naturally to them:

Even though it’s far from perfect, these models certainly seem to have an appreciation of how long the lines they generate are. Still, without changes to how they represent text, I would be surprised if they were ever able to get this consistently right every time.

Never Mind the Text, How Do You Justify This Project?

This project is undeniably a little bit silly. There aren’t many cases where you would need to generate perfectly justified monospace text, unless you’re planning on generating a lot of early 2000s style GameFAQs walkthroughs.

This was originally only meant to be a fun distraction on a long train journey, but it’s been a useful exercise for

learning more about how Hugging Face’s GenerationMixin works. In doing so, I’ve found a few places where I could

potentially contribute back to the library in future. In the mixin itself, there is a ToDo left over in the comments

about adding support for custom beams scoring functions, which would make these kinds of projects easier for future

developers. It also looks like there are some ideas in the Hugging Face documentation for other (undoubtedly more useful)

constrained beam searches which they suggest could make valuable contributions to the library.

Thanks to Andrew Webb for feedback on a draft version of this post.

Cite this post

@misc{wood2026beam,

author = {Wood, Danny},

title = {A Perfectly Justified Beam Search.},

year = {2026},

howpublished = {Blog post},

url = {https://echostatements.net/posts/2026/02/Constraining-LLMs-for-Perfect-Monospace-Text-Formatting/}

}

-

You might notice that the spaces have disappeared here. This is because spaces are treated slightly differently than other tokens by the tokenizer we use, so are absent from the standard decoding. ↩